Reviews

Artist Talk at the Helen Day Art Center, Stowe Vermont, February 28, 2004

If we were sitting outside on a summer day, I'd probably be tearing a leaf into a shape or rolling a blade of grass in my fingers. Perhaps you are the same way. Always making something. It never stops. The fingers are always busy though it doesn’t necessarily involve input from the brain.

The creative urge is something mysterious. Why some of us feel compelled to translate ideas into concrete metaphors is beyond understanding. Some of us just do. And when the urge comes in, there is not much to be done about it. You respond to it or you fight it. If you resist you become miserable. If you respond, you end up with a houseful of weird stuff like that exhibited here.

Given the slightest encouragement, such urges happily take over. You become like a person who has heard the voices of angels. For them, for ever after, all other sounds are insignificant. It is the same with art: it becomes the delicious taste you want more of. Oddly enough, the impulse to create has no correlation with the quality of the work. Many talented people have little or no urge to create, while millions of us with no discernible abilities are bursting with it.

Often unsuitable or even comic, the creative urge makes demands. I have known many artistic people who have refused sensible jobs for fear they’d be at work when the impulse came through. They'd miss the call. It starts badly and ends worse.

It can start early or late. The young artists in our household started while still in their cribs, finger-painting the walls with unmentionable substances. As their teeth erupted, they bit lacy decorative patterns in the vinyl car seat upholstery. When their little hands could hold scissors, they cut snippets from the drapes. There was plenty of fabric in the ragbag, but drapery material was what the impulse demanded.

Of course children today are raised differently than I was raised. If my children drew a line on paper, it was marvelous. Put it on the refrigerator! Clap your hands! Say "Wonderful!" This was not the style in my childhood. Back then, adults stayed as far from children as could be arranged. Shunned, we went off by ourselves. We built things. We had kingdoms and hierarchies and a Smelly God made from a peeled sassafras stick. We sniffed it and we bowed down to it. We built forts, rafts, tree houses, and burrows.

Today if a child desires a tree house, the parents hire an architect. They purchase lumber. It wasn’t like that then. Everything was salvaged and illicit, phenomenally messy, destructive, and thoughtless. None of our urges were ever described as art or given any encouragement. Encouragement? Why waste it on a child!

We didn’t have much but we had paper, pencils, and crayons. No coloring books; our mother wanted us to be original. We certainly were. We even found the prototype for coloring books, coating book illustrations with thick gobs of crayon. We did a beautiful job colorizing-- perhaps Ted Turner started in this way-- working heavily on some first editions of the Oz books. Since my sisters and I also read them till the pages came unhinged, their value was decimated in two ways, through our love of both literature and art.

My older sisters were fabulous artists. They specialized in what might be called comparison drawings, designed to tease or wound. The enormous power of art was clearly demonstrated in these painful works. A drawing of ratty goulashes labeled “YOUR SHOES!” was contrasted with an exquisitely rendered pair of diamond encrusted high heels. “MY SHOES.” Much younger, I couldn’t compete. My drawing of a ragged dress-- “YOUR DRESS,” looked sadly identical to the picture of “MY DRESS,” a glamorous ball gown.

At school, art was also used to consolidate power, but in a different way. You were graded on your ability to make an exact copy. Art meant drawing a pilgrim exactly as the art teacher did. She traveled from school to school supervising these copy sessions. Our school with its ten hole outhouses was not a prized posting. We were scabby, snaggle-toothed, dirty, ignorant, and none of us were good at her kind of art.

For our father, a scholar we visited from time to time, ART (all upper case letters) was work of unspeakable power created by great men touched by God. Where did this leave the rest of us, myself in particular? I had a head full of ideas. I liked to roll a blade of grass between my fingertips and color in books. But I full well knew I was not a great man touched by God. I didn’t need a mirror to be aware of my scrawny female body. My creations of rolled grass were not art, neither upper nor lower case.

In junior high, I somehow got my hands on a set of oil paints. You’ve never seen tinier, narrower tubes of paint. I had to work very thriftily or it all would be gone in seconds. When my mother studied these first oil small paintings she pronounced them “amateurish!” What else could the initial work of a child be? Why not say “Good for you!” or “Colorful!” Even “thrifty use of paint!” But her choice of words acted like a clamp on a hose. My work became even smaller, more tentative, and less public. Decades later, only Julia Cameron in The Artist’s Way could help me silence that grim voice repeating “amateurish!” ringing in my head whenever I put a brush to canvas.

In college, I continued to paint but did not venture to take art classes. I sent a still life to my father, the first time he saw one of my paintings. He hung it in the cellar behind a door, which was probably what it deserved, but by then it was too late for me. I was hooked. Obsessively hanging out in museums, I dreamed and breathed art. My friends were all artists and an art collector bought a painting from me for the princely sum of twenty five dollars. But he was the exception. Most who happened to see my work, unlike my mother, reacted with a resounding silence. So crushing a silence, indeed, that I referred to my paintings as “Gobstoppers.”

Once I began having artist boyfriends my work was discredited out of existence. I don’t say this to criticize them or for ‘poor me” value, but because it was just how things were. This was the pattern of the times. Women were supposed to use their energies to make a man great. I looked eagerly for a man willing to shoulder greatness, but they were all smoking dope and didn’t want to bother.

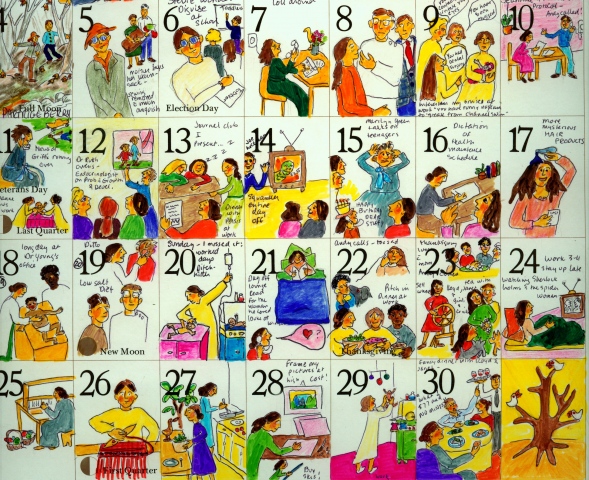

Without anyone to promote, I slumped along, satisfying the muse with diminutive offerings. My pictures shrank to teensy cartoons, one a day, on the pages of a commercial calendar. “What I did today.” This became my entire painterly outlet for some years. For public work, I made clay whistles, my mother's craft, because there I was safe from criticism. Who wants to criticize a toy?

When it got to the point that galleries and collectors bought all the whistles I could make, I felt encouraged. Ultimately making and selling whistles dominated my life, and somehow from behind that camouflage, the paintings began to grow. At their smallest, they were one inch square but they swelled, Hulk-like, to grander proportions.

But no matter what I was doing, my brain continued to burst with ideas. Fabulous theater sets with lots of scrims and clouds of vapor, outlandish furniture, artistic machines and games, gigantic sculptures. I wanted to build cities constructed entirely from the clear plastic used to make toothbrush handles. Beautiful, though none were ever made. And paintings, huge,dripping with paint, nothing in the least thrifty. Fresh ideas arrived daily. An unlikely field for such torrents, I scribbled them down in notebooks but seldom acted on them. I lacked courage, money, materials, skills, a place to work, and most vital, encouragement from others and permission from myself.

But even during the worst years, at least I kept a journal and the calendar, because there’s a thing about ideas. The more they’re recognized, the faster they come. Some soil is so fertile, every idea sprouts. Think of Leonardo da Vinci or Ben Franklin, both endlessly, oddly creative. Australia is their geographical equivalent with its bizarre landscapes, strange creatures, and unusual plants in marvelous excess.

I feel close kinship with those lucky and peculiar individuals who are especially fertile in this way. Anyone who painstakingly constructs an entire throne room for the Queen of Heaven fashioned from tinfoil? I'm on his side. Same for violins built entirely of match sticks, or crucifixes from trash.

You’ve all seen examples-- some of you have made them-- excruciatingly detailed models of heaven and hell in an unsuitable container like a dishpan. An entire house encrusted in buttons, or crockery, or pebbles. Depictions of Abe Lincoln fashioned from beetle carapaces. Or an inner city basket ball hoop atop a beaded telephone pole. What a fantastic statement about using sports to escape the ghetto. How many of us can sink a shot in so high a basket? It might also be a metaphor for the impossible world of Art, upper case, but it does not refer to creativity.

The world of off-kilter creativity is where I feel right at home. I’m thrilled when unsuspecting people, frequently to everyone’s embarrassment, are pushed into creations of ill proportioned grandeur. I knew a hillbilly musician who modeled a guitar, stunning in its detail, from tooth paste and toilet paper. Why this unusual creative focus? He was in jail, yearning for his guitar. When free, he'd never have made an artificial guitar at all. He would have played his actual guitar and been spared the less acceptable impulse. Captivity brought out the oddness in him, made him loam for a strange seed.

Whatever the cause, I strain toward such loaminess, always yearning toward art, lower case. I make whatever the muse directs me to make. Unlike scholars with their insistence on the rules and parameters defining Fine Art, (very upper case) for sheer creative force I cannot see a difference between a tribesman shaping a herd of mud cattle and Michelangelo chipping the David from stone. Each act is sacred regardless of material; mud or Carrara marble.

Does it matter if the mud cattle artist looses his enthusiasm for shaping his beasts, if he places them to dry on the Serengetti and never returns or makes another? If the marble chipper drops his chisel and walks away, leaving his work as just another lump of stone. It matters. Art rains on us from divinity and it should be done, not pushed aside.

But making art in America isn’t considered divine. This is a land where art is not really liked. Only the VALUE of art is valued. For the creator, it is a risky business in every sense of the word. Allowing yourself to be hijacked into loony creativity is a threat to the status quo. Art is dangerous, anxiety provoking, wrongheaded, and messy. Artists are unpredictable and unsafe to be around. Art is delusional, bringing temporary freedom from rules, especially those governing suitability and appropriateness. It is release from a cage. When working, one rides invincible on clouds of conviction, jealous even of time to eat, bathe, breathe, in the headlong necessity of it all. Artists and mystics are similar, always wanting MORE, more truth, more clarity, more light. And in responding to art, more truth, more clarity, more light is generated.

Calendar, November 1979