Reviews

Beast Wishes

Seven Days Art Review

By Marc Awodey

December 29. 2011

Creatures fly, squawk, slither and swim in Burlington’s Flynndog gallery this month — that is, in illustrations by Montpelier artist Delia Robinson. The drawings are from a new collection of poetry, a bestiary, by University of Vermont Italian professor Antonello Borra. In the Middle Ages, the Bestiarum vocabulum became a popular form of illuminated manuscript. A traditional bestiary was a catalog of animals, some fanciful and some real, each entry with a religious subtext. The medieval mind saw God in everything, so all parts of nature reflected aspects of Christian mysticism.

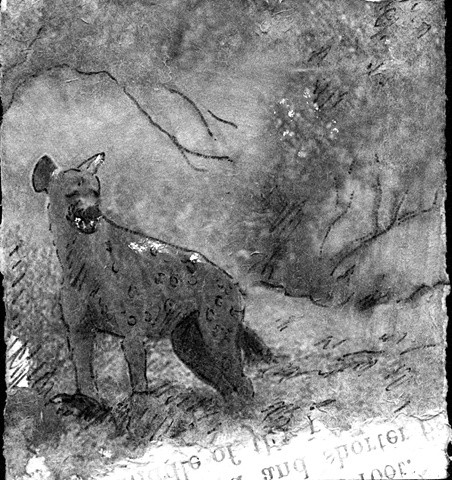

Borra’s new AlphaBetaBestiario is decidedly worldlier. Each of his poems has an existential subtext. For example, Borra’s verses about a lamb conclude with these words: “my innocent blood cries out to heavens / who knows if anyone is there to hear it?” Robinson’s corresponding lamb lies in the grass and looks straight at the viewer with a subtly anthropomorphic gaze. Other images in the black-and-white collection are more abstract, as Robinson adroitly modulates light and dark values.

Though the poetry is organized alphabetically (in its original Italian), this isn’t a child’s primer, and Robinson’s drawings are not the cute pictures of a little kid’s book. Rather, they are gestural and expressive. The artist concocted a diverse range of compositions that bring the animals to life, and employed a broad suite of lines, patterns and visual textures.

The Penguin takes a gracefully curved crescent shape, with snippets of text appearing in the background on what seem like torn and reassembled paper scraps. The Giraffe is also curved, but the animal is too big to fit in the square picture plane, so its neck appears as a matrix of black circles. Robinson placed it in front of a curious background featuring a colonnade and a door.

All 32 images in the book are displayed in the exhibit, framed and sited along the capacious eastern wall of the Flynndog. A copy of the book, splayed open to the appropriate page, hangs next to each illustration. Robinson describes her technique here as “faux etchings.” The drawings have been scanned and Photoshopped, then printed as giclées on high-quality paper.

Along the opposite wall, Robinson displays something of a retrospective of her earlier series, along with a few newer works. Though quite different, the two halves of the show work well together. In an oblique reference to traditional bestiaries, one of Robinson’s older series features large-scale images shaped like altarpieces; implied themes include captivity and metamorphosis.

“Lessons From History” is a large, altarpiece-style painting presenting a girl in the foreground looking at a castle on a distant hill. The clear blue sky becomes the interior of a dome encompassing the scene. Robinson’s paint is loose and watery, her hues simple and direct.

The vibrant acrylic-on-panel “Mangos and Macaws” is a more traditionally painted still life. It’s colorful and playful, with brightly plumed parrots in the right half ambiguously positioned in space — one is perched on a column. Architectural designs, such as machicolation and arches, are lightly inscribed in the background. The mangos are piled in a bowl at left, their roundness echoing the arches in the composition.

Arches, in fact, seem to be a recurring theme in Robinson’s work. The vertically composed “Magician and His Family” probably comes from the metamorphosis series. One brown bear and two polar bears sit in the interior corner of a red-walled, multistory atrium. Arches that seem to have grown into a forest appear on the first floor.

The 800-year-old Aberdeen Bestiary is the best-known text of the genre; it presents critters such as the Phoenix and Satyr as real, along with fanciful plants and minerals. While they are more naturalistic, Robinson’s illustrations in the AlphaBetaBestiario are equally intriguing.

By Marc Awodey

December 29. 2011